Learning Multithreading by Logging Asynchronously

Logging is a pretty basic concept which you get exposed to quite early as a programmer. The most fundamental programming exercises are usually about logging to a console or to a file. Multithreading on the other hand, has always been something that had a complex aura around it. This idea of building a multithreaded logger was given to me by Nick De Breuck when I asked him the following question: “How to learn multithreading?”.

If you need a production-ready solution, please use spdlog.

The project is open source. You can access the repo by clicking here, keep in mind that this is the version of the project that I used when writing the article.

Preliminaries

I am assuming a basic understanding of C++. I will not pay a lot of attention to implementation details, but to overall ideas and concepts.

Tracy is an open-source profiler packed with features useful when profiling games and other similar applications.

Multithreading Primitives

I am assuming a basic understanding of mutexes, condition variables, atomics and mutex wrappers (scoped_lock, unique_lock) present in the standard library. If any of those are unclear, please check the links provided here.

Test Environment

I test logging between single and multithreaded solutions by aggressively logging from a 3D model loading function in order to observe the performance of logging. I log each solution to both console and file to compare the results. This serves as a way to check the results against the “ground truth”, represented by the single-threaded output:

Logging Diagram

flowchart LR

A[Binary Load<br/><i>1x</i>] --> B[Mesh Start<br/><i>15x</i>]

B --> C[Index Log<br/><i>~17,000x</i>]

C --> D[Attributes<br/><i>45x</i>]

D --> E[GPU Upload<br/><i>15x</i>]

E --> F[Summary<br/><i>1x</i>]

style C fill:#ff6b6b33,stroke:#ff6b6b,stroke-width:2px

About Hammered Engine

“Hammered” is a personal project of mine where I explore anything that piques my interest. Currently it uses C++23, however, the concepts discussed are not tied to C++ and could be applied to any other language.

Single-Threaded Logger

Sink Architecture

A sink is an object that will process a message and “print” it to a destination that can be written to as well as flushed. To flush means the function will return only after the message was written by the sink. This destination could be a file called log.txt, or the console we all had to write to when learning to code. As you can imagine, flushing is often the slowest part.

This is why

endlis not as fast as using\n;endlwill also flush the console buffer, which is way slower than only doing a newline.

The diagram below shows the overall architecture of the logger and sink system:

classDiagram

class BaseSink {

<<abstract>>

+Sink(LogMsgView msg)*

+Flush()*

}

class ConsoleSink {

-Mutex m_mutex

+Sink(LogMsgView msg)

+Flush()

}

class FileSink {

-ofstream m_file

-Mutex m_mutex

+Sink(LogMsgView msg)

+Flush()

}

class BaseLogger~Mutex~ {

+vector~shared_ptr~BaseSink~~ sinks

#string m_name

#Level m_level

#Mutex m_mutex

+Log(Level, string_view)

+Flush()

+Debug(format_string, args...)

}

BaseSink <|-- ConsoleSink

BaseSink <|-- FileSink

BaseLogger o-- BaseSink : contains

Sink Implementation

To call the sink object we need to pass a LogMsgView, an object that has the message we want to send and any other information we might find useful. One could add or remove as much as they need:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

struct LogMsgView

{

Level level; // Debug, Warning, Error etc.

std::string_view loggerName; // could have multiple loggers, each could have the same or different sinks, so it is important to differentiate between them

std::string_view payload; // the message!

time_point timestamp; // useful for debugging

std::thread::id threadId; //only relevant in a multithreaded context

};

C++ uses the concept of a

string_view, you can think of this as a read-only pointer to a string object with some utility functions and size of the string.

We can use an abstract class as our blueprint for making various kinds of sinks:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

class BaseSink

{

public:

virtual ~BaseSink() = default;

virtual void Sink(LogMsgView msg) = 0;

virtual void Flush() = 0;

};

template<typename Mutex>

struct ConsoleSink : BaseSink

{

void Sink(LogMsgView msg) override

{

HM_ZONE_SCOPED_N("ConsoleSink::Sink");

std::scoped_lock lock(m_mutex);

std::println("{}", msg.payload);

}

void Flush() override

{

HM_ZONE_SCOPED_N("ConsoleSink::Flush");

std::scoped_lock lock(m_mutex);

std::cout.flush();

}

private:

// allows us to see contention for this lock in Tracy

// this is equivalent to:

// Mutex m_mutex;

HM_LOCKABLE_N(Mutex, m_mutex, "ConsoleSink");

};

// File sink is exactly the same, except for the code handling the file

template<typename Mutex>

struct FileSink : BaseSink

{

explicit FileSink(const std::string& fileName) : m_file(fileName) {}

void Sink(LogMsgView msg) override

{

HM_ZONE_SCOPED_N("FileSink::Sink");

std::scoped_lock lock(m_mutex);

m_file << std::format("{}\n", msg.payload);

}

void Flush() override

{

HM_ZONE_SCOPED_N("FileSink::Flush");

std::scoped_lock lock(m_mutex);

m_file.flush();

}

private:

std::ofstream m_file;

HM_LOCKABLE_N(Mutex, m_mutex, "ConsoleSink");

};

HM_ZONE_SCOPED_Nmarks a profiling zone in Tracy.HM_LOCKABLE_Nwraps a mutex so Tracy can visualize lock contention. These are thin wrappers around Tracy’s C++ API.

Note that there may be times when different wrappers for log messages are needed. The one above does not own its message, and uses a read-only approach, which has the advantage of no-memory allocations for the string it holds.

Base Logger

To build a logger, one needs to wrap the sinks inside an API that allows the user to call the basic sink and flush functions. A few templated functions will also help us make a thread-safe and a non-thread-safe version.

Below I am using scoped_lock which is used to acquire and release it the mutex when the object lifetime goes out of scope.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

//this is a struct that makes the mutex be accepted to strip thread-safeness

struct NullMutex

{

void lock() {}

void unlock() {}

bool try_lock() { return true; }

};

template<typename Mutex>

struct BaseLogger

{

virtual ~BaseLogger() = default;

virtual void Log(Level level, std::string_view msg)

{

//can set the level to higher to filter messages

if (level < m_level)

return;

//create our message

LogMsgView view {.level = level,

.loggerName = m_name,

.payload = msg,

.timestamp = clock::now(),

.threadId = std::this_thread::get_id()};

//only one thread can log one logger object at a time

std::scoped_lock lock(m_mutex);

for (const auto& sink : sinks)

{

sink->Sink(view);

}

};

virtual void Flush()

{

//only one thread can flush one logger object at a time

std::scoped_lock lock(m_mutex);

for (const auto& sink : sinks)

{

sink->Flush();

}

}

template<typename... T>

void Debug(std::format_string<T...> fs, T&&... args)

{

//profiling function from Tracy

HM_ZONE_SCOPED_N("Log::Debug");

Log(Level::Debug, std::format(fs, std::forward<T>(args)...));

}

//other functions like debug

//sinks can be added here via polymorphism

std::vector<std::shared_ptr<BaseSink>> sinks;

protected:

std::string m_name {"LoggerName"};

Level m_level {Level::Debug};

//null or std::mutex

Mutex m_mutex;

};

//shorthands

//thread-safe

using LoggerMt = BaseLogger<std::mutex>;

//single-threaded, no overhead

using LoggerSt = BaseLogger<NullMutex>;

Mutexcan be eitherstd::mutexwhich makes the code thread safe, orNullMutexwhich is an empty implementation of a mutex construct. This makes it so C++ removes all the multithreading primitives and removes the overhead associated with it.

Then we can create a new logger that logs both to file and console like so:

1

2

3

auto logger = std::make_shared<LoggerSt>();

logger->sinks.push_back(std::make_shared<ConsoleSinkSt>());

logger->sinks.push_back(std::make_shared<FileSinkSt>(path));

Global Logger and Utilities

The log function can then be use to log to both sinks, a global logger object and helper functions could be written, below is an example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

// macro that selects which logger to define as DefaultLogger

#define HM_LOGGER_TYPE 0

#if HM_LOGGER_TYPE == 0

using DefaultLogger = LoggerSt;

#elif HM_LOGGER_TYPE == 1

using DefaultLogger = AsyncLogger;

#endif

// singleton

inline std::shared_ptr<DefaultLogger>& GetGlobalLogger()

{

static std::shared_ptr<DefaultLogger> instance;

return instance;

}

inline void SetDefaultLogger(std::shared_ptr<DefaultLogger> logger)

{

// move is a more efficient way to "assign" variables in C++

GetGlobalLogger() = std::move(logger);

}

inline std::shared_ptr<DefaultLogger> GetDefaultLogger()

{

return GetGlobalLogger();

}

template<typename... T>

void Info(std::format_string<T...> fs, T&&... args)

{

if (auto logger = GetDefaultLogger())

logger->Info(fs, std::forward<T>(args)...);

}

Execution Diagram

The flow of a single log call looks like this:

sequenceDiagram

participant Main as Main Thread

participant Logger

participant Console as Console Sink

participant File as File Sink

Main->>Logger: Log::Debug("message")

activate Logger

Note over Logger,Console: Sink(msg)

Logger->>Console:

activate Console

Note right of Console: println() blocks

Console-->>Logger:

Note over Logger,Console: done

deactivate Console

Note over Logger,File: Sink(msg)

Logger->>File:

activate File

Note right of File: writing to file blocks

File-->>Logger:

Note over Logger,File: done

deactivate File

Logger-->>Main: return

deactivate Logger

Profiling Results

The model that is loaded is called A Beautiful Game which contains 15 meshes and logs every 100th index value. Click here to see the overview diagram of the logs.

“A Beautiful Game” © 2020 ASWF/MaterialX Project (original), © 2022 Ed Mackey (glTF conversion). Licensed under CC BY 4.0.

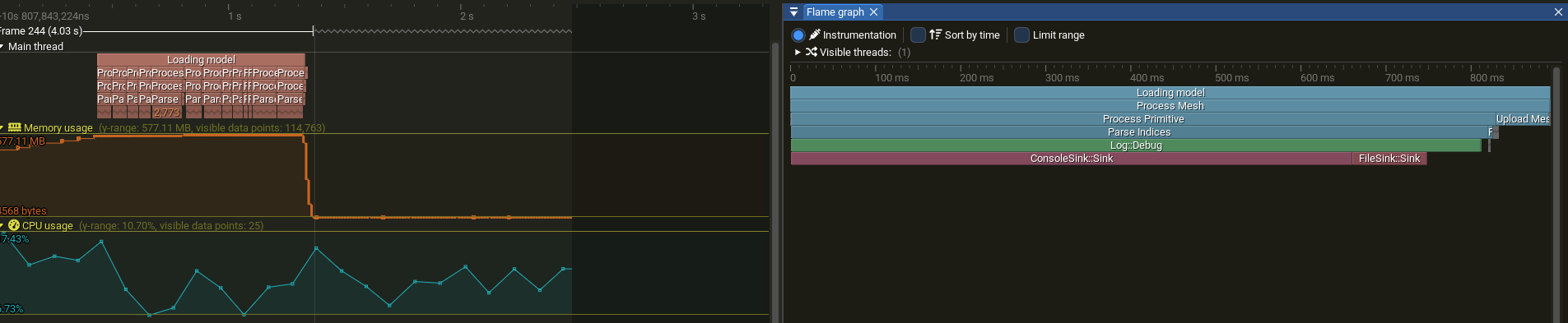

Running Tracy on our load function for this logger will give us the following results:

If you want to inspect the file yourself using Tracy:

Here we can see that our main logging function, which is Log::Debug is mainly taking most of the time on the “sink” of the console. This happens because the function will wait for println to return. Now the important question: Will multithreading make it faster?

Naive Multithreading Attempts

Thread Pool

We could try to multithread this directly via a ThreadPool:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

#pragma once

#include <mutex>

#include <queue>

namespace hm

{

// based on

// https://stackoverflow.com/questions/15752659/thread-pooling-in-c11

class ThreadPool

{

public:

//constructors ...

//generic jobs, can be anything

void QueueJob(const std::function<void()>& job);

//make sure that all threads are done with their work and join them

void Shutdown();

//are any jobs still being done?

bool Busy();

private:

std::vector<std::thread> m_threads;

//

std::atomic<u32> m_activeJobs;

//while loop that keeps spinning

void ThreadLoop();

bool should_terminate = false; // Tells threads to stop looking for jobs

std::mutex queue_mutex; // Prevents data races to the job queue

std::condition_variable mutex_condition; // Allows threads to wait on new jobs or termination

std::queue<std::function<void()>> jobs;

};

} // namespace hm

This class aims to provide a general way to multithread various tasks. It works under a few rules of thumb in multithreading:

- it is best to not create more threads than the number of hardware threads we support;

std::thread::hardware_concurrency() - creating new threads is slow, therefore, we initialize them once and then put them to sleep while we have no work; this is what happens in the

ThreadLoopalso known asWorkerLoop - threads that are always active with no work to do are “punished” by the OS, our application may get less time because of that and suffer a performance hit; a condition variable is used to put all threads to sleep and wake one up when work is available

- a mutex is needed when accessing the queue of jobs, otherwise we might get critical data races which will make the behaviour of our programme non-deterministic at best and crash at its worst

- on

Shutdownwe should finish all the jobs in the queue, then join all the threads together.

I am deliberately omitting the implementation of this generic

ThreadPool, because I would like to explain in detail how a specialized thread pool could work for the async logger. If you are still curious you can find the.cppfile here.

The hot-spot for logging messages becomes:

1

2

3

4

5

pool.QueueJob(

[i, idx = indices.back()]()

{

log::Debug(" Index[{}]: {}", i, idx);

});

This is a lambda, that allows us to queue the logging as a job.

Tracy Results

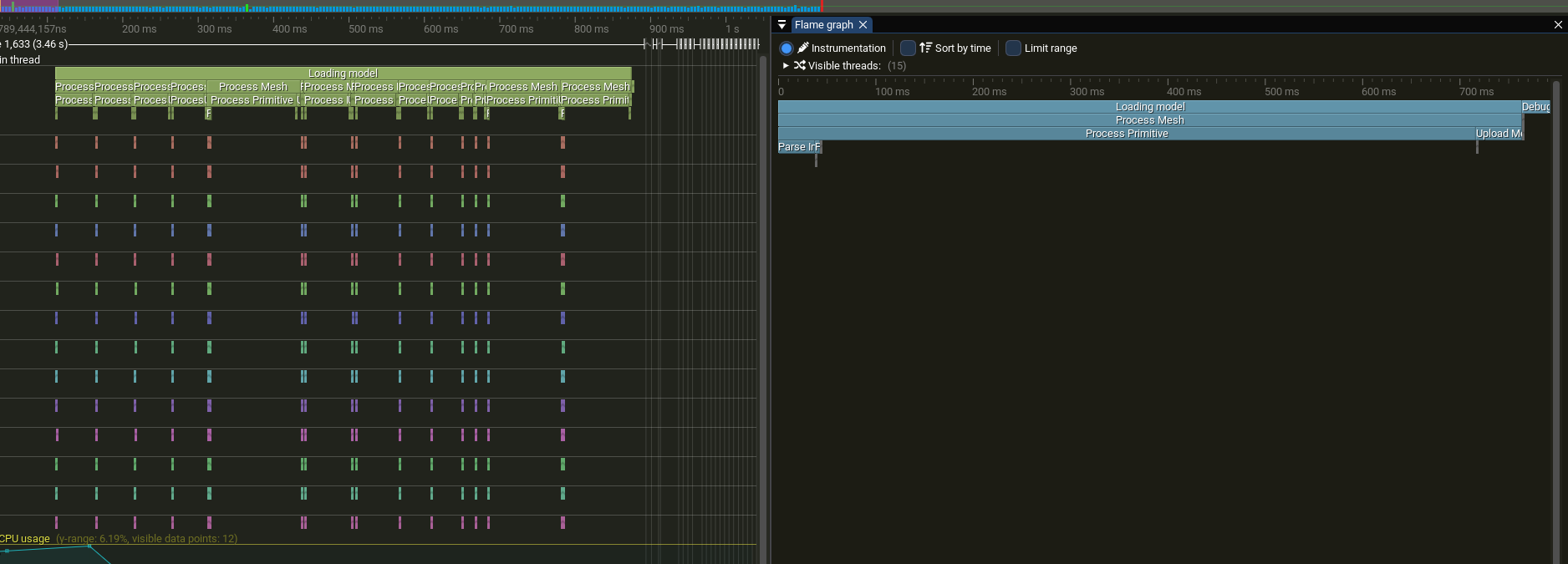

The result is orders of magnitude slower, not only that, but our output is no longer in the correct order.

Contention between Threads

Threads are waiting on each other for the mutex. The overhead is obviously bigger than the single-threaded result, as mutex and the other primitives have a noticeable overhead.

sequenceDiagram

participant T1 as Worker 1

participant T2 as Worker 2

participant T3 as Worker 3

participant M as Mutex

participant C as Console

Note over T1,M: lock()

T1->>M:

activate T1

Note right of M: Worker 1 holds lock

Note over T2,M: lock()

T2-->>M:

Note over T2,M: blocked

Note over T3,M: lock()

T3-->>M:

Note right of T3: blocked

Note over T1,C: println()

T1->>C:

Note over T1,M: unlock()

T1->>M:

deactivate T1

Note over T2,M: lock() acquired

M-->>T2:

activate T2

Note right of M: Worker 2 holds lock

Note over T2,C: println()

T2->>C:

Note over T2,M: unlock()

T2->>M:

deactivate T2

Note over T3,M: lock() acquired

M-->>T3:

activate T3

Note right of M: Worker 3 holds lock

Note over T3,C: println()

T3->>C:

Note over T3,M: unlock()

T3->>M:

deactivate T3

Buffered Logger

We could have much faster results by reducing the time it takes to log a message. The correct order is also possible if we pass the timestamp from the main thread before queuing the ThreadPool.

1

2

3

4

5

6

auto ts = log::clock::now();

pool.QueueJob(

[i, idx = indices.back(), ts]()

{

log::Debug(ts, " Index[{}]: {}", i, idx);

});

Despite the clunky API for passing the time to a function about logging, we are nearly done optimizing it. I created a new SortedLogger that inherits from the BaseLogger class. This will only add messages to a std::vector and only on the Flush call it is going to sort and call the slow Sink functions. It is important that now we have an owning std::string of our message, otherwise we will get invalid data when the string that was passed goes out of scope.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

//LogMessage uses a std::string

std::vector<LogMessage> buffer;

//we need to pass the time if we want the correct order

void Log(Level level, std::string_view msg, time_point ts)

{

if (level < m_level)

return;

LogMsgView view {.level = level,

.loggerName = m_name,

.payload = msg,

.timestamp = ts,

.threadId = std::this_thread::get_id()};

std::scoped_lock lock(m_mutex);

//we do not log now, but add to a vector of messages

buffer.emplace_back(view);

}

void Flush() override

{

//on flush we sort all messages based on the timestamp

std::scoped_lock lock(m_mutex);

std::sort(buffer.begin(), buffer.end());

//now we call the sink function

for (const auto& msg : buffer)

{

for (auto& sink : sinks)

{

sink->Sink(msg);

}

}

//clear buffer and flush all sinks

}

What we lose is the real-time output from earlier. To even get the output, we have to rely on the user to call the Flush after the thread-pool has finished all its tasks.

1

2

// ThreadPool.Busy() returns false, so all tasks are done

indexLogger.Flush(); // Outputs sorted by timestamp

At least the order is the same as in the single-threaded one. This could be made even faster, since I did not even pre-allocate memory for our buffered vector.

log_multithreaded_correct_order.txt

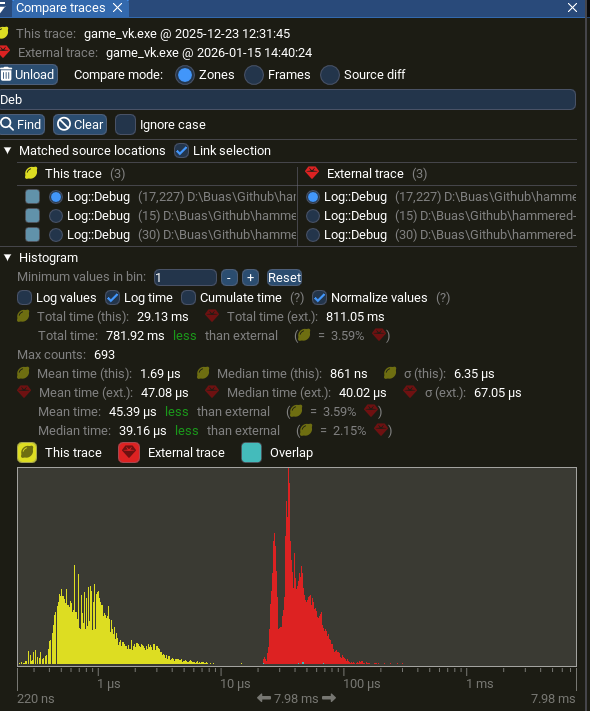

This approach is marked as yellow (faster), compared to single-threaded which is red (slower):

The buffered approach fits well with separate threads with subsystem multithreaded architectures: AI, physics, rendering etc., each maintaining their own buffered logger, flushing at the end of the frame. Otherwise, it is a cumbersome API, most of the time you need to see the output in realtime. This is where the async logger becomes appealing: it queues messages very fast and does the slow processing later on a background thread.

Async Logger

Before tackling the async logger, one should understand its core data structure: the circular queue (also called a ring buffer). Its purpose is similar to the std::vector used in the Buffered Logger section, however, it provides more flexibility and makes it possible to multithread adding messages as well as processing them. From a performance standpoint it avoids memory reallocations, the queue is pre-allocated once, and the user can configure overflow behavior when it fills up.

Circular Queue

This library uses a circular queue wrapped with thread safety and pre-allocated memory in order to avoid reallocations at runtime. The main concept that is used in async logging is to separate queueing of messages from writing them to the sink. They offer three overflow policies when the queue is full:

- Block: The calling thread waits until space becomes available

- Discard New: New messages are dropped if the queue is full; existing messages are preserved

- Overwrite Oldest: New messages overwrite the oldest unprocessed messages in the queue

This is one of the reasons a circular queue is used. It handles what happens when the memory allocated is full. A circular queue maintains a fixed-size buffer with head (next element to pop) and tail (next empty slot) indices that wrap around. In the constructor, the maximum capacity is increased by one to keep track if the queue is full. This means that when the tail index is equal to the head, the queue has run out of space. When overwriting, both indices are advanced following each other.

Diagram

Here’s a visualization of the queue state with three elements added:

flowchart TD

subgraph Queue["Buffer State - Initial"]

s0["[0] A"]

s1["[1] B"]

s2["[2] C"]

s3["[3] ___"]

s4["[4] ___"]

s5["[5] ___"]

s6["[6] ___"]

s7["[7] RESERVED"]

end

head["head = 0"] -.-> s0

tail["tail = 3"] -.-> s3

style s7 fill:#ff6b6b33,stroke:#ff6b6b

After pushing 5 more elements (D, E, F, G, H) with the “overwrite” policy, the oldest element (A) gets dropped and the queue wraps:

flowchart TD

subgraph Queue["Buffer State - Full"]

s0["[0] RESERVED"]

s1["[1] B"]

s2["[2] C"]

s3["[3] D"]

s4["[4] E"]

s5["[5] F"]

s6["[6] G"]

s7["[7] H"]

end

head["head = 1"] -.-> s1

tail["tail = 0"] -.-> s0

style s0 fill:#ff6b6b33,stroke:#ff6b6b

Queue Implementation

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

template<typename T>

class CircularQueue

{

public:

explicit CircularQueue(u64 maxItems)

: m_maxItems(maxItems + 1),

m_buffer(m_maxItems) // one item reserved as marker for full queue

{

}

void PushBack(T&& item)

{

//assume queue capacity is valid before calling this

m_buffer[m_tail] = std::move(item);

m_tail = (m_tail + 1) % m_maxItems;

// if full, overwrite oldest element

if (m_tail == m_head)

{

m_head = (m_head + 1) % m_maxItems;

++m_overrunCount;

}

}

// ...

private:

u64 m_maxItems = 0;

u64 m_overrunCount = 0;

u64 m_head = 0;

u64 m_tail = 0;

std::vector<T> m_buffer;

};

LogThreadPool

Similar to the generic ThreadPool shown previously, this implementation uses mutexes and condition variables to ensure thread safety. A wrapper can be built around the CircularQueue in order to make it thread safe and still have a version without the overhead. Spdlog uses a mpmc_blocking_queue to offer this flexibility. It implements the three overflow policies mentioned earlier, applied to Enqueue and Dequeue. For brevity only the blocking version of these two is written in code below.

MPMC stands for multi producer multi consumer, and means that it will be thread safe for multiple threads to write and read at the same time.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

// blocking dequeue without a timeout.

void Dequeue(T& popped_item)

{

HM_ZONE_SCOPED_N("LogQueue::Dequeue");

{

// unique_lock will allow the condition variable to lock/unlock the mutex

std::unique_lock lock(m_queueMutex);

// if queue is empty, wait

m_pushCV.wait(lock,

[this]

{

return !this->m_queue.Empty();

});

popped_item = std::move(m_queue.Front());

m_queue.PopFront();

}

m_popCV.notify_one();

}

// try to enqueue and block if no room left

void Enqueue(T&& item)

{

HM_ZONE_SCOPED_N("LogQueue::Enqueue");

{

std::unique_lock lock(m_queueMutex);

m_popCV.wait(lock,

[this]

{

return !this->m_queue.Full();

});

m_queue.PushBack(std::move(item));

}

m_pushCV.notify_one();

}

An important aspect of this thin wrapper is that it uses condition variables for push and pop actions that are separate. This improves performance by only waking up threads that have work to do, rather than all waiting threads. This is then used by a specialized ThreadPool which deals with logging. This owns the mpmc construct, and is similar otherwise to the previous pool used in the buffered approach.

The overall flow from log call to output becomes:

flowchart LR

subgraph Main["Main Thread"]

A[Log::Debug] --> B[PostLog]

end

B --> C[(MPMC Queue)]

subgraph Worker["Worker Thread"]

C --> D[Dequeue]

D --> E[BackendSink]

end

The “worker loop” in this case is responsible for processing messages from the queue. Messages can have types (LOG, FLUSH, TERMINTE) and are required to use std::string, rather than their non-allocating counterpart: std::string_view. Otherwise, we may get invalid data.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

bool hm::log::LogThreadPool::ProcessNextMsg()

{

HM_ZONE_SCOPED_N("ProcessLogMsg");

AsyncMessage incoming_msg;

m_queue.Dequeue(incoming_msg);

switch (incoming_msg.type)

{

case AsyncMessageType::LOG:

incoming_msg.asyncLogger->BackendSink(incoming_msg.msg);

return true;

case AsyncMessageType::FLUSH:

//manual flush

incoming_msg.asyncLogger->BackendFlush();

return true;

//this will make it so it waits for all threads to finish their work before shutdown

case AsyncMessageType::TERMINATE:

return false;

}

return true;

}

An implementation detail worth noting:

AsyncMessageowns theAsyncLoggerviashared_ptr. This handles the scenario where a logger is destroyed while messages referencing it still exist in the queue.

The AsyncLogger still inherits from the same base class as the other loggers in my project. The main Log function has changed to sending the message to the LogThreadPool as below. The PostAsyncMsg inside LogThreadPool is very similar to its Process counterpart with the only difference that instead of using the Pop functions, it uses the Push ones.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

void AsyncLogger::Log(Level level, std::string_view msg)

{

HM_ZONE_SCOPED_N("AsyncLogger::Log");

if (level < m_level)

return;

LogMsgView view {.level = level,

.loggerName = m_name,

.payload = msg,

.timestamp = clock::now(),

.threadId = std::this_thread::get_id()};

//get the log thread pool and handle what to do if it is not initialized

if (pool)

{

pool->PostLog(shared_from_this(), view, m_overflowPolicy);

}

}

Performance Comparison

The tests below were performed with a very large allocated queue of 8,192 × 5 = 40,960 entries (each storing a u64) and a single worker thread. This was chosen as one consumer thread guarantees the same order of logs and minimizes thread contention, although I have not explored the possibility of more than one background thread.

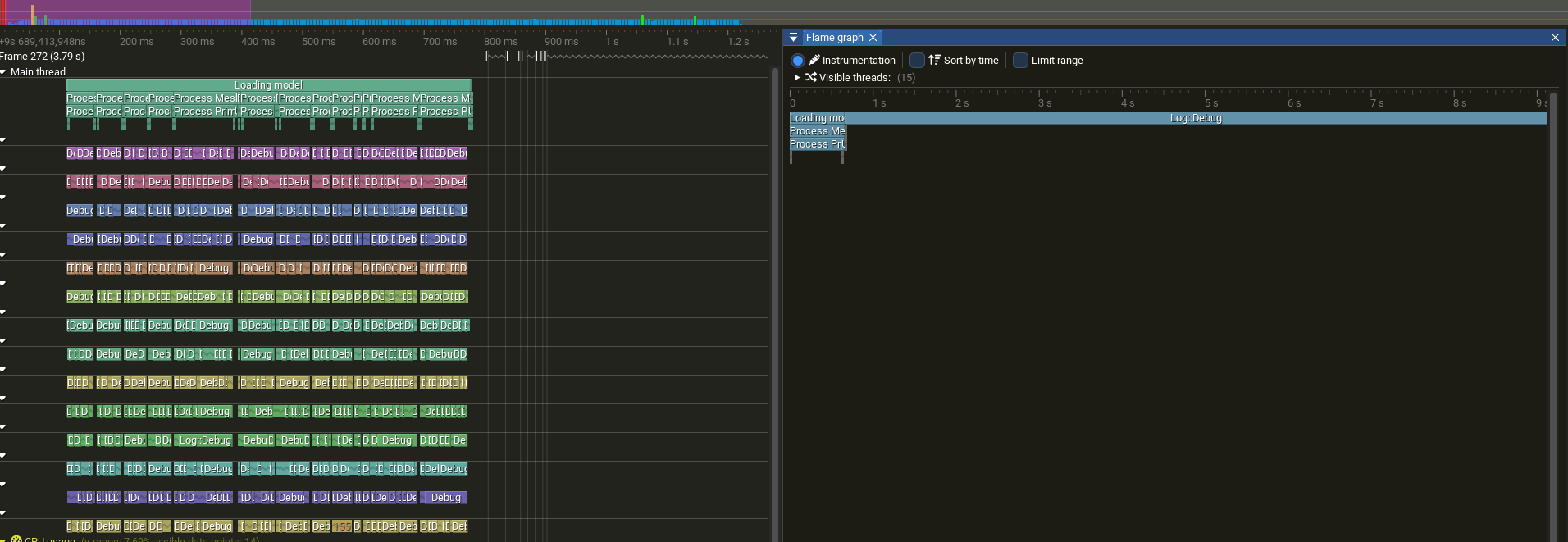

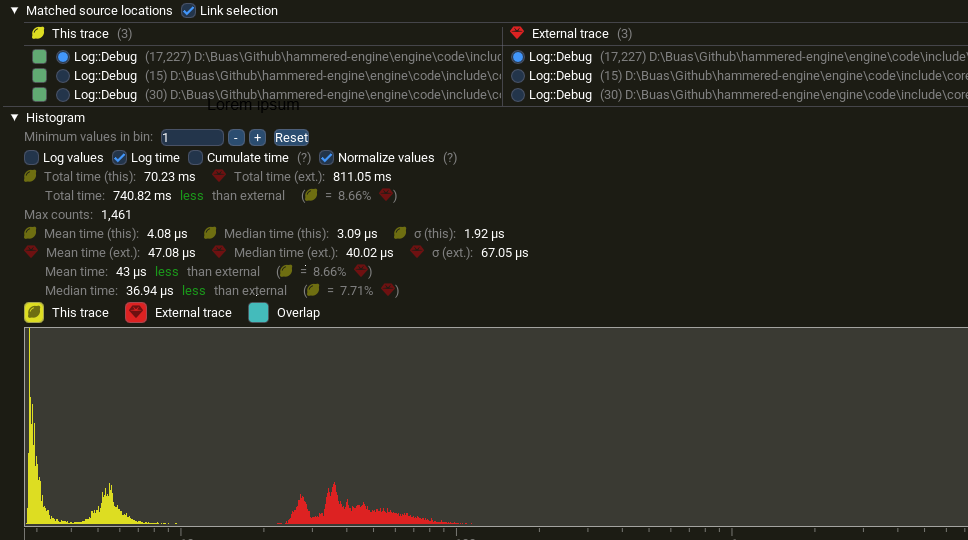

Log::Debug is considerably faster with async logger (yellow) than single-threaded logging (red)

Log::Debug is considerably faster with async logger (yellow) than single-threaded logging (red)

| Approach | Log::Debug Total | Log::Debug (mean) | Speedup |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-threaded | 811 ms | 47 µs | baseline |

| Async Logger | 70 ms | 4 µs | ~11× |

| Buffered + ThreadPool | 29 ms | 1.7 µs | ~28× |

The buffered approach is fastest (~28×) but requires manual flushing and delayed output. The async logger (~11×) has realtime-ish output while still keeping the main thread responsive.

The async logger reduces per log overhead from 47 µs to 4 µs; the main thread spends 92% less time on logging.

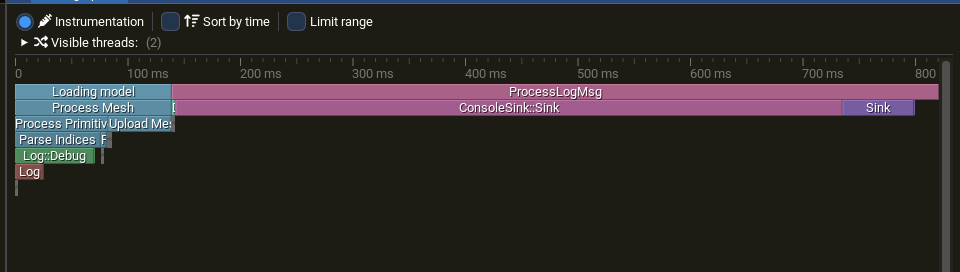

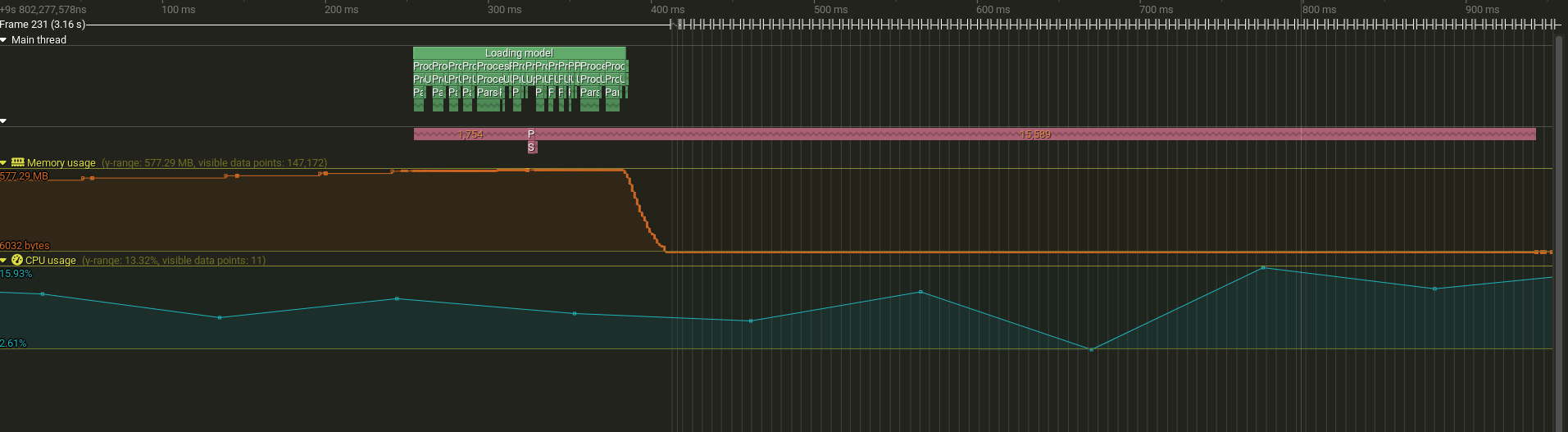

In Tracy you can clearly see when the main thread finished sending all the messages and the other thread is still processing them later at runtime.

Timeline showing main thread (green) finishing logging related calls while worker thread (pink color) continues processing queued messages

Timeline showing main thread (green) finishing logging related calls while worker thread (pink color) continues processing queued messages

This is the same graph for the async approach. You can notice how overall the calls are marginally under 1 second, however, the Log::Debug is taking considerably less, because it is not tied to the console sink anymore.

In conclusion, an async logger provides a flexible and performant solution for lots of logging. It decouples the queue of a message from the sink operation and it allows various multithreading scenarios. One could have multiple producers as in the UI, Physics, AI example earlier and still use 1 consumer thread. Or if order of logs is not important, one could add as many threads as needed to the consumer part.

To summarize the progression of approaches explored in this article:

flowchart LR

A[Single-Threaded] -->|add buffering| B[Buffered Thread Pool]

B -->|add async queue| C[Async Logger]

A -.- A1[Base performance, Ordered]

B -.- B1[Fastest, Weird to use]

C -.- C1[Fast, Realtime-ish]

References

Libraries & Tools

- spdlog — Fast C++ logging library

- Tracy Profiler — Frame profiler

Books

- Game Engine Architecture by Jason Gregory — The multithreading chapter

- C++ Concurrency in Action by Anthony Williams

Learning Resources

- Mike Shah’s Multithreading Series — YouTube playlist

- cppreference — Thread support library

Final Words

I made this article based on a self study project I did as a third year programmer at Breda University of Applied Sciences for the Creative Media and Game Technologies bachelor. Thanks for reading my article. If you have any feedback or questions, please feel free to email me at bogdan.game.development@gmail.com.